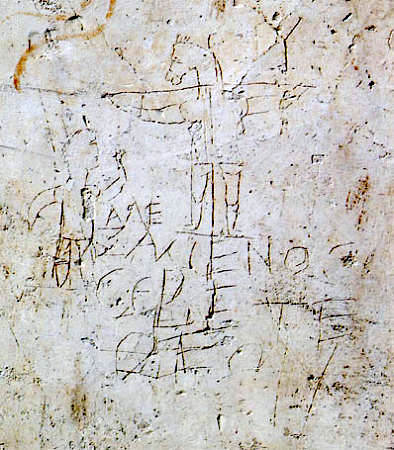

The graffito itself depicts a donkey-headed human form on the right being crucified with a human worshiper to the left. An inscription accompanies the images which reads alexamenos sebete theon, or “Alexamenos worship (or worships) God.” Disregarding the problematic Greek verbal form (as written an imperative, but many scholars believe that is a mistake made by an inscriber unfamiliar with the intricacies of the Greek verbal system), the name suggests that the human form is that of an otherwise unknown ancient worshiper named Alexamenos.

What makes this graffito particularly important is that it is the earliest known representation of the Crucifixion of Jesus. Scholars debate when the crucifixion of Jesus became central to early Christian veneration, most suggest that it was not until after the fourth century. The date of this image could be anywhere between the late first century and the late third, with most scholars who studied the image leaning toward a later date. With either date, the image also provides some evidence of the kind of discrimination faced by early Christians within their Roman context before the abolition of such practices in the early fourth century by the emperor Constantine.

Among the many accusations leveled at Christians during this period of persecution was the connection of Christianity and Judaism with the practice of “onolatry” (or donkey-worship). Descriptions of these accusations are discussed by the early Christian heresiologist Tertullian in the late second century. He mentions that these groups were accused of worshipping a god that had the head of a donkey, he even mentions a story of a Jew who had converted to Christianity being forced to walk around the north African city of Carthage carrying the image of a man with a donkey’s ears and hooves with the label “the God of the Christians born of an ass.”

Tertullain, Ad nations, 1:11

In the next accusation we are found guilty not just of abandoning our communal faith, but of adding on a monstrosity of superstition. Some of you have entertained the dream that our god is actually the head of an ass. Cornelius Tacitus first launched this fantasy in the fourth book of his Histories where he recounts the Jewish war. Starting with the origins of the Jewish people, he traces the source of their religion and its name. He relates how the Jewish people, hard-pressed for water and wondering abroad in desolate places, were delivered by following the lead of a herd of wild asses thought to be in search of water after feeding. For this reason the likeness of this animal is worshiped by the Jew. This is why I believe that we Christians, being linked to the Jewish religion, are associated with the same image...Perhaps this is your charge against us that in the midst of all these indiscriminate animal lovers, we save our devotion for asses alone!

Tertullain, Ad nations, 1:14

There is now a new rumor about our God going the rounds. Recently a most depraved individual from Rome, your city, had defected from his own faith and allowed his skin to be shredded by wild beasts. Every day he would hire himself out for viewing while his skin was stripped. He would carry around a picture directed against us with the heading "Onocoetes," meaning Donkey Priest. It was a picture of a man wearing a toga and the ears of the donkey with a book in hand and one leg ending in a hoof. And the crowd believed this Jewish man. Who else plants the seed of our infamous reputation? As a result the whole city is talking about the Donkey Priest. Since this rumor has been around since yesterday, it lacks any authority of time and is compromised by the character of its author.

The image of the Alexamenos graffito raises important questions of religious tolerance, the representation of Jesus within early anti-Christian art, and the response of worshipers to derogatory implications.

Tertullian probably was not responding to the Alexamenos graffito per se, but the incidents he mentions, Tacitus' charge of onolatry, and Josephus' refutation of the charge of onolatry in _Against Apion_ lead me to suspect that the Alexamenos graffito is earlier rather than later. I have my own thoughts on Uncle Cephas

ReplyDelete